The system wants us to fail

By D. Woodin

After sixteen hard years, my beautiful son has mostly recovered from schizophrenia. He still hears voices, but he knows they aren’t real. He takes his medications every two hours because he wants to be sane. He has finally stopped self-medicating. He spends his time creating music, writing screenplays, helping me with projects, and going on adventures with me. In September, he walked his sister down the aisle, taking the place of their dad who died six months before.

But we have been forced to fight both the mental health and criminal justice system to get to this sweet place, and sometimes I have a shadowy, dark feeling the system wants us to fail.

On a hot June day in 2020, I lay bleeding in my bathing suit in a lounge chair by our pool after my psychotic son stabbed me with a pocketknife seven times. His violence was not foreshadowed, but unbeknownst to me he had missed a dose of his monthly anti-psychotic shot that had kept him stable for six years prior to this incident. It was the very shot I had fought the “Patient Has Rights” system to get.

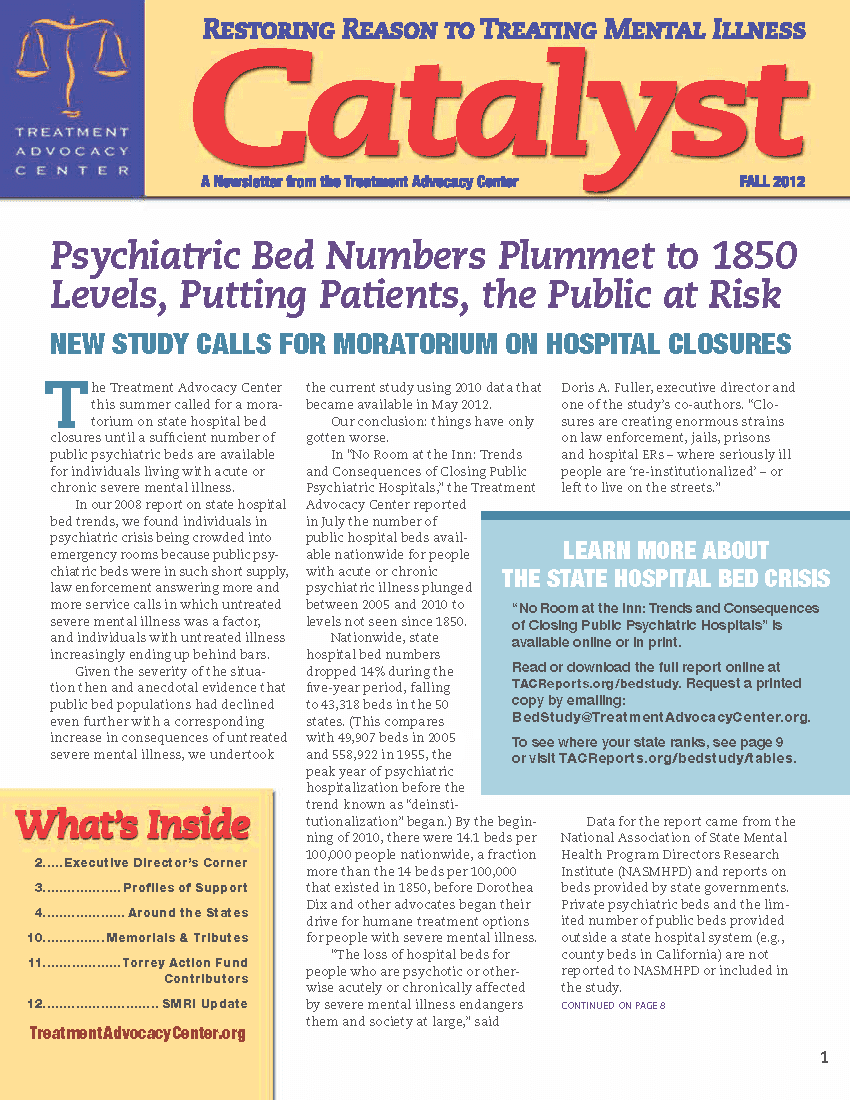

That fight was a familiar, well-worn story fraught with panicked calls to the police, emergency room doctors, and health care professionals. Ten years ago, a psychologist I had hired to give me resources for my son told me point-blank: “You have to help yourself. This will kill you.” Her suggestion was to check myself into a $50,000 facility to rest and relax, because there was basically no help for my son in a broken system.

Fast forward to the days leading up to that fateful June day. My son had missed his anti-psychotic injection because, when he went for his appointment, a computer failed at the community mental health center. He told me he returned the next day, but because he thought the medication interfered with his creativity, he actually hadn’t returned. I double checked, but even though he had signed a HIPAA release, I was never told he didn’t return for his shot, and my e-mail inquiry to a clinic family liaison came back five days later with a non-answer.

I spent a week in the hospital with a collapsed lung and a severed radial nerve before my daughter found out the truth: my panicked son had returned to the health center the morning of the attack, realizing he was psychotic. It’s a miracle he did that. But he was turned away, because by then he was eight days late and needed a doctor’s approval. My son’s schizophrenia does not allow him to wait for treatment.

My injuries were not the worst part. The three horrible years he spent in county jail with the threat of an 11-year sentence hanging over his head like a guillotine was agonizing, but even that was not the worst part. It was the terrible realization that the current mental health system would never adequately support us, even after the hell it had put us through.

While my son was in jail, I consoled myself with the thoughts, “At least now the mental health professionals know what is at stake. If by some miracle he gets out of jail, we will be given every available resource for my son to succeed. We will not have to go it alone anymore, ever.” When he was finally released with seven years of probation after being forced to plead guilty to attempted murder, I told myself the fire we had walked through was probably necessary and worth it.

Instead, he was released from jail without meds. A medication adjustment by the clinic at the very beginning of his release temporarily made my son unstable. I handled it, driving him to the hospital while he narrated his hallucination to me. But that incident caused the staff at the clinic to lose their bearings. Suddenly, I was the enemy, and they tried thereafter to undermine me. I was screamed at by the case manager when I wanted my son to be admitted briefly to a mental facility while the meds were adjusted: “Insurance won’t pay for med changes! I am done with you!” He went behind my back to try to force my son into a terrible board and care, which I knew would derail his progress.

My son was told the staff didn’t want me in the waiting room when he came in for his injection, because he should be responsible for his own care. The new director asked for a meeting and a brief history, and as I was obligingly answering his questions, he condescendingly called me a “helicopter mom.” I finally used my own money to find a nurturing social worker at a different place further away, and my son decided to go on oral medications, so he never has to be dependent on a facility giving him the injections again.

I learned we are alone on this journey. If there is to be change, we must create it. If we have the support of friends and family we are truly blessed, but the system is largely not going to save us. There is much hope, but we have to take on this Herculean task alone.

At a fabulous haunted house the other night, I asked my son in amazement why he wasn’t scared like he used to be. “Mom, it’s not real,” he said. “I’ve been through far scarier things that actually are real.”